Following on from his much-shared Twitter thread , in this piece, Neil Butler, a maths teacher and Special Educational Needs Co-ordinator at North Wicklow ETSS, outlines the chronic underfunding of the Irish education system and explores what this means for the future.

“It can be difficult to know exactly where we stand, how good our education actually is compared to the rest of the world. Bigger or smaller countries face different challenges and have different advantages. Countries with more money can do more for their children, those with less can do less.

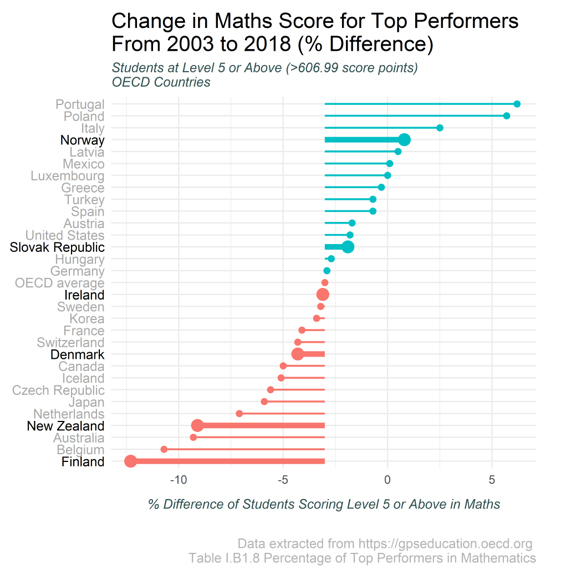

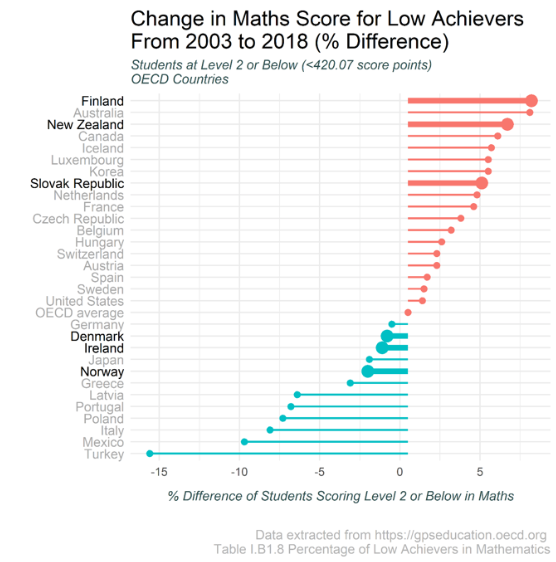

If we take a look at our children’s maths scores, we can see that the amount of our students performing at the highest level has not increased at all since 2003. This is most definitely not good. Could it be that despite over a decade of reform, our best and brightest aren’t getting any more numerous? Or could it be that there are scores of children with untapped excellence that have been let down by our education system over the last 15 years? On a brighter note the number of students performing at the lowest levels in maths fell drastically. This is great and is a testament to the work of all involved during the particularly difficult conditions brought about by the economic crash of 2008 and subsequent programme of austerity.

Government Expenditure

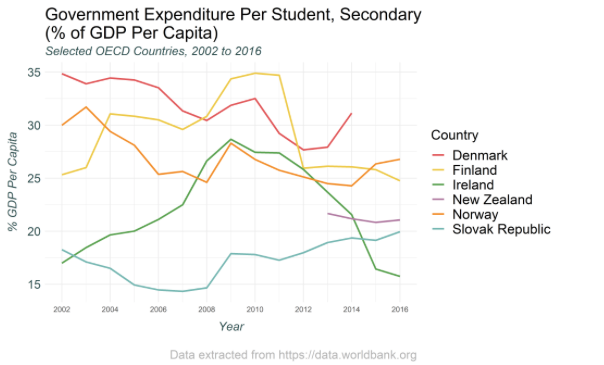

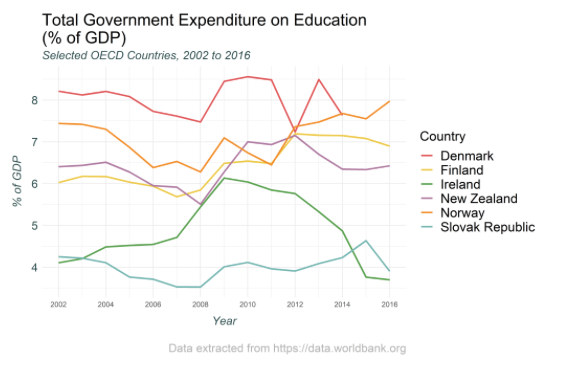

But these scores hide something incredibly worrying about the Irish education system – we are spending far, far less on our children than all of the other countries of similar make-ups to our own. Consider the following graph showing the government expenditure on our secondary school children as a percentage of GDP, and that of comparable nations such as Denmark, Finland and New Zealand.

In 2009 our expenditure fell off a cliff and hasn’t stopped dropping. This looks bad. If we look at the total government expenditure on education the situation is even more bleak. Norway is outspending us by a factor of two. Finland and New Zealand are spending about 1.5 times that which we are. Denmark look to be massively outspending us also based on the most recent information from the World Bank.

How have we kept our results so steady when our education system has been stripped bare?

It is teachers that are stepping into the breach.

Teachers are having to do more with less. A huge amount of previously departmental administrative work has been “devolved” to schools; work teachers have not been given time in which to complete. Junior Cycle reform (and the coming Senior Cycle reform) have placed a greater emphasis on teachers to provide more varied and intricate learning experiences (active, cross-curricular, real-world, engaging) along with additional assessment and reporting requirements.

Not only that – we have bigger classes. When budget time comes around, we need to listen for the key phrase “pupil-teacher ratio”. If this isn’t mentioned, then nothing has changed. This from Minister Joe McHugh is misleading at best (sourced here).

‘The 2018/2019 school year saw an increase of over 6000 teaching posts in our schools compared to the 2015/2016 school year.’

The 6000 ‘extra’ posts over the previous three years are due to increased needs presenting in an increasing population: the support given to each child individually has not increased. Similarly, the information on pupil-teacher ratio takes all pupils in a school and compares them to all teachers. There are increased teachers, but this is due solely to an increase in need for Special Education Teachers, not that class sizes have reduced – they have not.

In order for there to be an actual increase in support for our children, schools need to explicitly be given more teachers per pupil. The pupil-teacher ratio for post-primary schools is 19:1 (the school gets one teacher for every nineteen students). This has not changed since at least 2010/11.

Similarly, ‘more SNAs’ does not mean we are expanding our SNA service to take care of a greater range of need. It simply means there are more children presenting in school with the already agreed-upon set of care needs. The government is not doing more because it cares, it is keeping things exactly the same because it has to. Exactly the same, in this case, for our schools actually means worse.

But where will these teachers come from? New teachers (that is, teachers appointed since 2011) are being paid at a lower rate for the same work than that which their more experienced colleagues receive. People no longer want to be teachers. Let me rephrase: people are seeing the economic realities of a teacher’s salary and sky-high rents and deciding not to become teachers. It is almost impossible to find suitably qualified teachers in a number of subject areas (maths, physics, chemistry, modern foreign languages).

I know we have some of the absolute best educators in the world in our system. I see what my colleagues in school and around the country do every day and it is awe inspiring. We will retire or retire early because it is not worth it, we will burn out because all the extra responsibility and consequence will take its toll. We won’t be there for your children because the system will have failed us. We need support.

I entered teaching in 2007. I had a decade of austerity-induced, insecure, part-time work. I was one of the lucky ones, despite the stress this insecurity placed on me and my family. I desperately hope that my children won’t be in school when a decade of (albeit delayed) austerity-induced systemic failure occurs. If we don’t do something about our investment in education soon, I fear they will be.

Please think of the most vulnerable person you know and vote in their best interest. Please make education your priority this general election 2020.

Thanks to Philippa Wilkes for data visualisation and insight.